Repowering wind turbines adds generating capacity at existing sites

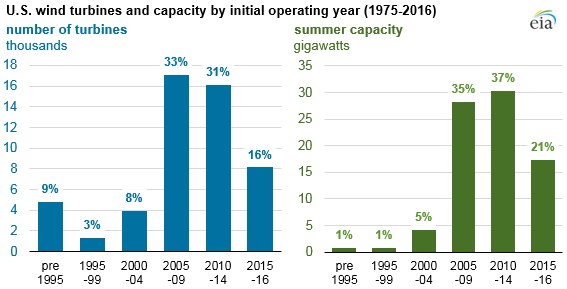

Repowering older wind turbines, which involves replacing aging turbines or components, is becoming more common in the United States as the turbine fleet ages and as wind turbine technology advances. Newer turbines tend to be larger and installed at greater heights, allowing for more capacity per turbine. About 12% of the wind turbines in the United States were installed before 2000, but these turbines make up only 2% of the installed wind electricity generating capacity.

Federal production tax credits provide an incentive to increase electricity generation from existing wind turbines. In December 2015, the production tax credit (PTC) was extended until the end of 2019. The four-year extension and legislated phase-out of the PTC is expected to encourage many asset owners to repower existing wind facilities to requalify them to receive another 10 years of tax credits. A facility may still qualify for the PTC as long as at least 80% of the property’s value is new. This provision allows many owners to repower existing turbines without completely replacing them.

Fully repowering wind turbines involves decommissioning and removing existing turbines and replacing them with newer turbines at the same project site. Full repowering has mostly occurred in California, where many turbines were installed at high-wind sites before 1990.

Partial repowering involves leaving some portion of the existing wind turbine and replacing select components. By partially repowering, owners can increase hub heights and rotor diameters to produce more energy.

Although wind turbines are designed with lifespans of between 20 and 25 years, wind capacity factors decline with age as mechanical parts degrade, according to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Technologies Market Report. The United Kingdom’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council in 2014 indicated that, on average, the output of wind turbines declines by 1.6% each year. Repowering can increase the output of a wind facility, improve reliability, and extend the life of a facility by taking advantage of advances in wind turbine technology.

Newer turbines tend to rotate much more slowly and quietly than older, smaller turbines, turning at 10 to 20 revolutions per minute (rpm) instead of 40 to 60 rpm. Slower wind turbine rotations alleviate issues such as bird mortality and shadow flicker.

Repowering generally requires significantly less investment compared with new projects. However, repowering wind turbines does present some challenges. For example, the risk of failure may increase when reusing components such as towers and foundations that were designed for smaller turbines. Other challenges may include renegotiating power purchase agreements, interconnection agreements, and leases.

According to General Electric (GE), the largest wind turbine installer in the United States, repowering wind turbines can increase the fleet output by 25% and can add 20 years to turbine life from the time of the repower. General Electric has repowered at least 300 wind turbines, and the company expects this market to grow. MidAmerican Energy recently awarded a contract to GE Renewable Energy to repower as many as 706 older turbines at several wind farms in Iowa. After repowering, each turbine is expected to generate between 19% and 28% more electricity.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has indicated that annual U.S. wind repowering investment has the potential to grow to $25 billion by 2030. EIA data indicate that three projects are currently planned for repowering: Mendota Hills, LLC in Illinois and Sweetwater Wind 2 LLC in Texas are scheduled for repowering in 2018, and Windpark Unlimited 1 in California is scheduled for repowering in 2022.

In addition, Rocky Mountain Power has announced its intent to repower wind turbines in Wyoming and is currently awaiting a public hearing on the issue. NextEra Energy is planning to repower two wind farms in Texas by the end of this year.

More information about electric generators in the United States is available in EIA’s Annual Electric Generator Report. The early release of the 2016 version of this report was made available in August; the final version is scheduled for release in November.

Principal contributor: Suparna Ray

Tags: electricity, generation, renewables, wind