Negative prices in wholesale electricity markets indicate supply inflexibilities

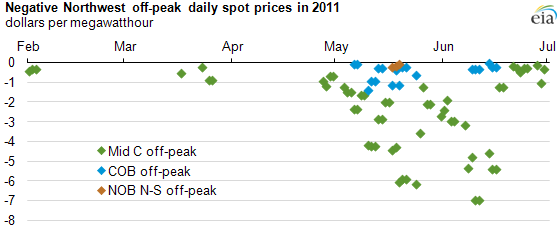

Note: Off-peak is 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. on Monday through Saturday and all hours on Sunday. Mid C is Mid-Columbia, COB is California-Oregon Border, and NOB is Nevada-Oregon Border.

Wholesale electricity markets sometimes result in prices below zero. That is, sellers pay buyers to take the power. This situation arises because certain types of generators, such as nuclear, hydroelectric, and wind, cannot or prefer not to reduce output for short periods of time when demand is insufficient to absorb their output. Sometimes buyers can be induced to take the power when they are paid to do so.

Negative prices are rare in bilateral markets and more common—albeit still unusual—in Regional Transmission Organizations (RTO). In this article, we focus on negative bilateral spot prices, which occur predominantly in the Pacific Northwest. Negative prices in RTOs will be the subject of a follow-on article.

Technical and economic factors may drive power plant operators to run generators even when power supply outstrips demand. For example:

- For technical and cost recovery reasons, nuclear plant operators try to continuously operate at full power.

- The operation of hydroelectric units reflects factors outside of power demand, for example, compliance with environmental regulations such as controlling water flow to maintain fish populations.

- Eligible generators can take a 2.2 ¢/kWh or $22/MWh production tax credit (PTC) on electricity sold. This means that some generators may be willing to sell their output for as low as -$22/MWh to continue producing power. Typically, wind generators are the largest such group in any region.

- There are maintenance and fuel-cost penalties when operators shut down and start up large steam turbine (usually fossil-fueled) plants as demand varies over a day or a week. These costs may be avoided if the generator sells at a loss to attract a buyer when demand is low.

In these situations, generators may seek to maintain output by offering to pay wholesale buyers to take their electricity. These situations are most likely to occur in markets with large amounts of inflexible nuclear, hydro, and/or wind generation. In the Pacific Northwest, abundant hydroelectric resources have been augmented in recent years with significant wind capacity. This combination of generating sources has increased the likelihood of the conditions leading to negative prices.

In 2011, InterContinental Exchange (ICE, a widely-used, internet-based, bilateral trading platform for matching buyers and sellers) reported 84 instances of negative prices, 80 of which were in the Pacific Northwest. Each of these 84 instances was for ICE's off-peak product for power delivered during the periods of time when electricity demand is lowest (including a block of eight hours overnight as well as all day Sunday).

The chart above shows the 80 instances of negative prices reported in the Northwest, primarily at the Mid-Columbia pricing point on the Washington-Oregon border. The weighted annual average, off-peak price at Mid-Columbia in 2011 was $14/MWh. Negative prices occurred in the Northwest during the spring and early summer when low-cost hydroelectric generation exceeded local demand by a wide margin. The excess power was transmitted primarily to California. But for short periods of time, the transmission system delivering the power outside the region could not handle the excess electricity. Competition among generators in the market consequently drove down prices, even below zero. This competition was particularly fierce in 2011 because it was an unusually plentiful hydro year in the Northwest.